Walker Evans, Hero of the Vernacular Style

A landmark exhibition argues that the photographer’s approach to image making goes far beyond documentary.

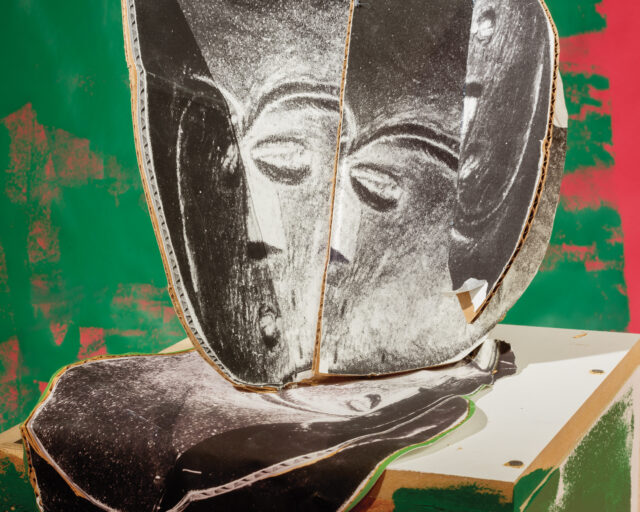

Walker Evans, Resort Photographer at Work, 1941

Last fall, shortly after the opening of Walker Evans at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, curator Clément Cheroux and I sat down for a conversation about the massive retrospective, which he originally organized for the Centre Pompidou. We spoke about the organizing thematics of “vernacular as subject” and “vernacular as method,” Evans as a proto-conceptualist, and the risks of including objects from Evans’s own collection of weird and grisly photographs.

Sarah M. Miller: Framing Evans’s work through the vernacular allowed you to sidestep the thorny question of what documentary is, and what our expectations of it are, while also presenting to American audiences a less familiar history of documentary: the avant-garde’s. Could you expound on that framework? How did you choose it?

Clément Chéroux: The challenge was to show the work of Walker Evans, including his iconic photographs, but also to build something new in the approach. Especially in Europe, Evans is mostly known as a documentary photographer. I’ve been thinking about this question of the documentary style, and the question of the vernacular.

The two larger categories we have in photography are art and non-art. On one side, you have the art photographer, and on the other side, the vernacular. Everything that is not art is vernacular photography: documents, snapshots, architecture photographs, postcards, photographs of tools for catalogs, et cetera. Evans used the term “documentary style.” Documentary photography is only part of a larger category known as the vernacular. This is the reason why I proposed the concept of a “vernacular style.”

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: What you’re saying is that you don’t accept this common division that puts documentary in opposition to art. It makes more sense to put vernacular in opposition to art, and to see documentary as that which bridges or deliberately brings the vernacular into art?

Chéroux: No, for me, documentary is part of the vernacular. In twentieth-century photography, the line is between what is art and what is not art. What is not art is the vernacular, which includes documentary photography, amateur photography, scientific photography, everything. For me, documentary photography is a small part of vernacular photography.

Miller: So, style is the bridge. As someone who also works on the history of documentary photography, I always stress that artists associated with “documentary style” chose the form or the look of information, rather than the function of actually transmitting information, and deployed those forms in order to change what kind of art photography could be. The aesthetic of information allowed artists to play with the deadpan, and to reject the overtly expressive. I saw that argument played out in the show, which I loved.

Chéroux: The fact that Evans was recognized as a photographer using the documentary style is a historical phenomenon. When Evans became more recognized in the 1980s and ’90s, especially in Europe, he became the hero of the documentary style. Most of the photographers were working in this style—the whole Düsseldorf school, the Bechers, Ruff, Gursky. Contemporary photographers need predecessors.

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: How did you divide the ideas of “vernacular as subject” and “vernacular as method” to structure the two parts of the exhibition?

Chéroux: Almost everybody who has written about Evans says he was trying to define the essence of American culture through the vernacular. But the word “vernacular” is never very well defined.

Miller: You give it a historically and linguistically specific definition in your catalogue essay.

Chéroux: The etymology was useful to understand the definition of vernacular: it brings us back to the Roman Empire where the Latin word for slave was verna, so the vernacular is something that is useful. Vernaculus means a slave that is born in the house, so vernacular means something that is domestic. Along with the domestic comes the idea of the local, and throughout history the meaning of the local has extended to the village, to the town, to the region, and to the whole country. According to the Roman civil code, the slave is at the bottom of the hierarchy. So, the vernacular is always something that is low.

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: It’s easy to see how the utilitarian and culturally low are manifest in Evans’s subjects. But how does this understanding of the vernacular translate to method?

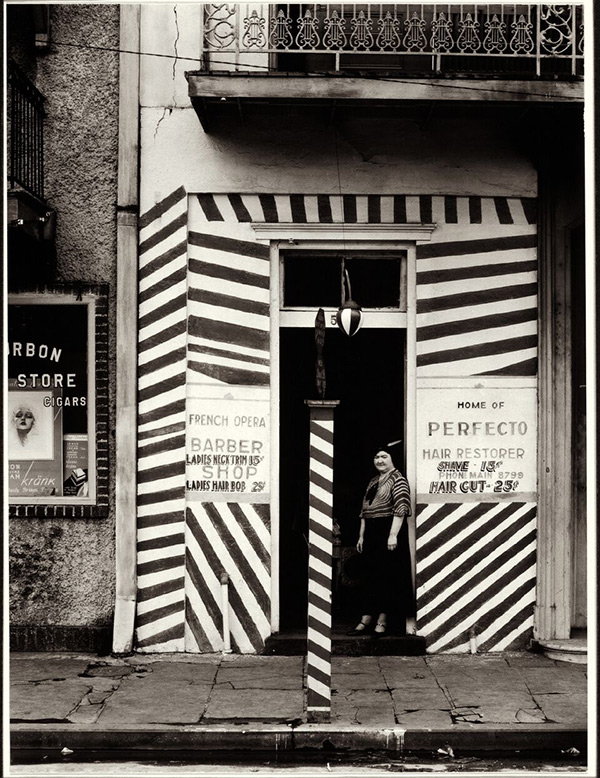

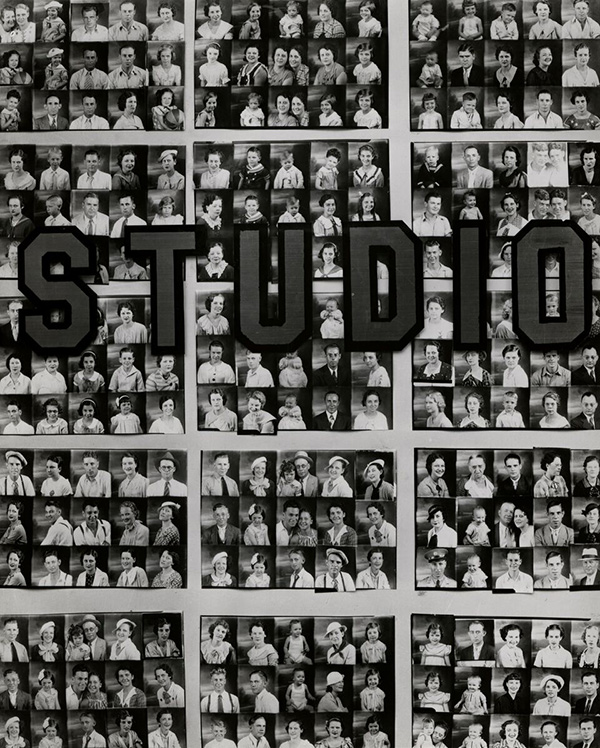

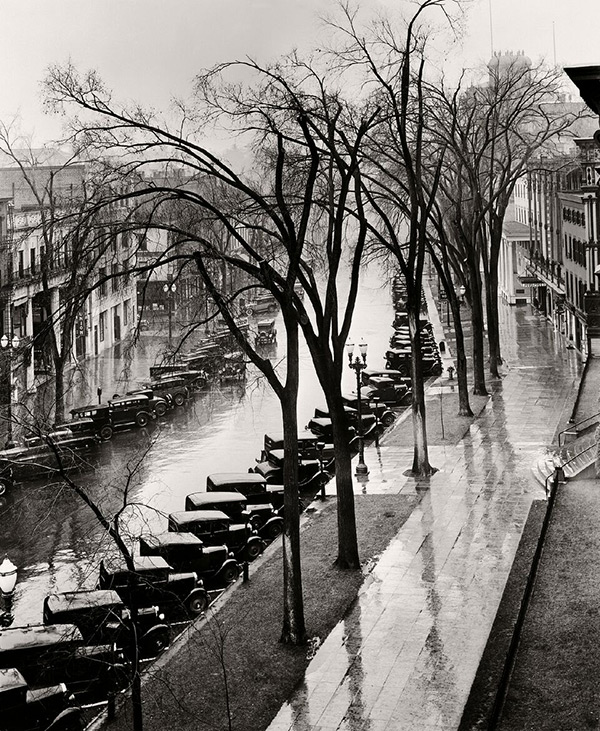

Chéroux: The first part of the exhibition is about what is in front of the lens, and the second is about what is behind the lens. The second part is really about the method with which Evans chose to photograph the vernacular. I realized that Evans, when he was choosing a subject, approached it by mimicking a style of photography, which was that of an applied photographer. For example, when he was taking photographs of the small-town Main Street, he was choosing the vantage point and the cropping of a postcard photographer. When he was taking shots of doorways or wooden churches, he photographed them as if he were an architecture photographer or a survey photographer. Some series he made are related to studio portrait photography; others are related to architectural photography, postcard photography, snapshot photography, et cetera.

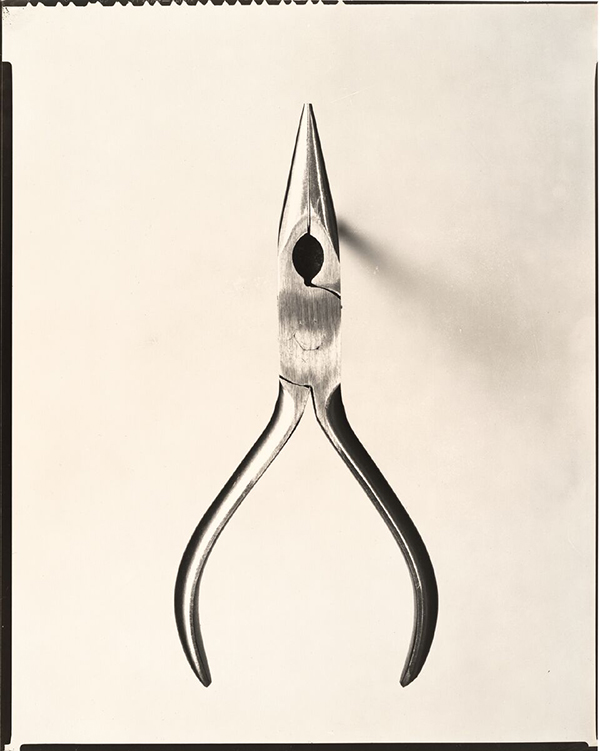

What’s the best way to photograph a tool? Stieglitz would photograph it one way, Man Ray another way. Evans decides to do it as if he were a catalogue photographer: no shadows, no angles, no distortions, very straight. Every time Evans was interested in a subject, he would choose a way to depict it that was related to a certain kind of vernacular photography. The vernacular as a subject, plus vernacular as a method, combine to make the vernacular as a style. That’s really the idea I would like to demonstrate through this exhibition.

What’s the reason why Evans chooses not to play the artist? Stieglitz, for example, was really playing the artist. Evans was hiding himself as an artist by mimicking vernacular photography. And that’s quite difficult to explain to the public. He is an artist, but an artist who is not playing the artist; and on the contrary, he is playing the non-artist. This is the reason why I think that Evans is a conceptual photographer. The vernacular as a subject explains why Evans is perceived as a precursor of Pop Art. Rauschenberg, Warhol, and Lichtenstein also chose the vernacular as a subject. But if you think about the vernacular as a method, it explains why Evans was perceived by many photographers of the 1970s—“artists using photography” like Dan Graham—as a kind of precursor.

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: Part of what’s so difficult about Evans is that he comes with a controlling mythology. It’s all about impersonality and removing the artist from the picture. But critics recognized as early as the ’30s that Evans was creating another form of auteurism. Many of the reviews of American Photographs (1938) noted that he could appropriate any subject at all into “an Evans.” In the ’70s, that idea was taken to extremes and used against him by critics, namely Martha Rosler and Allan Sekula. But will it ever be possible to address that idea in a museum context? Will it ever be possible to mount an exhibition that doesn’t proceed from Evans’s self-definition as an artist, his posture of self-suppression?

Chéroux: Maybe a way to answer your question is by raising the issue of the political in Evans work. When I started working on this Evans retrospective, I was almost sure I would find some connection with the Left. Evans was friends with a lot of people who were leftist, people like artist Ben Shahn. But after reading letters and texts, and going through his photographs, I quickly understood that Evans was not interested in politics. The fact that he was interested in the sharecroppers, the fact that he was photographing the effects of consumerism, the effects of industrialization, all of these things, was not a political approach. That was an aesthetic approach. It’s a Baudelairean approach.

Miller: I’ve always thought of Evans as an astute cultural critic, but one who would refuse to call himself a political critic. His cultural criticism comes from a political viewpoint, to be sure. But there is no political agenda, only a political viewpoint.

Chéroux: Yes, that’s it. In French we say “la politique” and “le politique.” So, the first one is being engaged in politics, and the second one, just by changing the pronoun, is being concerned, but not part of the movement.

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: When you played out the argument about vernacular as method through the exhibition, did you have any worry that it could flatten the distinctions between different kinds of assignments—for example, Evans’s work for the Museum of Modern Art on African masks, or for Fortune—versus a highly individual project like the subway photographs?

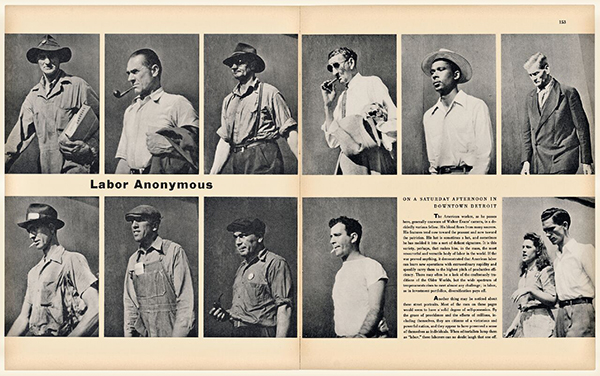

Chéroux: The only one that I would really consider as a commission is the African masks. All of the projects for Fortune were his own ideas. I mean, there was no editor saying to him, “Please make a project about tools,” or “Please make a project about taking photographs from the train.” He was choosing the subject, he was taking the photographs, but then also cropping the photographs, doing the layout, and writing the text. We should not consider the projects for Fortune as commissioned. It’s totally different from what Cartier-Bresson was doing for the press. When Cartier-Bresson was sent on assignment, he was taking the photographs and then sending everything to his agency. He was not editing. Evans was really in control of everything.

Miller: So for you, it’s a way to demonstrate not only that he’s a conceptual photographer, but also that there’s a conceptual continuity to projects that otherwise might look like very different parts of his career and different frameworks for making and distributing.

Chéroux: Yes, the magazine projects were another way to make art. He was doing that since the ’40s. Again it makes him a precursor to conceptual artists of the ’60s and ’70s, people like Dan Graham, or other artists who were treating the magazine as the best way to disseminate their ideas. So, for me, if it’s not commissioned, it’s a piece of art in itself. That is why I wanted to have the magazines on the wall, and not in the middle of the room in a vitrine.

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: You’re emphasizing that the magazine really is the art; it’s Evans’s chosen presentation of the art.

Chéroux: If you think about the ’40s through ’60s, he was doing more projects for Fortune than exhibitions. In a way, it was more important to show the magazines than to show American Photographs. There were a lot of strong choices in planning this exhibition. American Photographs is a great book, but the magazine work is as important. American Photographs is for me a kind of Bible of the vernacular. But I really didn’t want to reduce the whole exhibition through the book.

Miller: In the first week of the show, I raised concerns about the inclusion of a lynching photograph in the exhibition. I would have been alarmed no matter what, but I suppose I was on heightened alert because I was preparing to bring my students. Were you surprised that it could elicit such a strong reaction?

Chéroux: Yes, that was a bit of a surprise for me, and that’s a cultural difference between the United States and France, where the exhibition originated and was presented for the first time. You know, I’ve only been here nine months, and I’m learning every day about these questions. The newspaper photograph that you mentioned is among the press material that Evans clipped from papers and kept in a scrapbook titled Pictures of the Time: 1925–1935. He collected these images as a young man, when he was developing his visual style and sourcing thousands of references including fine art images, news images, vernacular and applied photography, postcards, street photography, and graphic design. We don’t know exactly why he kept these images, he never expressed himself about that, but we believe that they are an important part of Evans’s artistic process. We have included a label alerting visitors that there is challenging content in one gallery. For me, the question is why he was so interested by disturbing graphic images—not only that one, but also the electric chair, the people who were assassinated in Cuba.

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: I understood that context. I had already talked with my students about how the interest in the document of the ’20s was, in some cases, as Pierre Mac Orlan said, the notion that a photographic knowledge of the world is cruel. Evans was fascinated by the weird and barbaric insight that photography inadvertently provided into modern life, and collected images that his generation would have called documents for that reason. But it’s a hard line to walk here, where the work of racial terrorism those lynching photographs were manufactured to carry out can feel very alive. Especially in a season where we’re debating Civil War memorials and people are voicing the right not to be attacked by acts of white supremacism in public—no matter what historical context they were erected in or published in.

Chéroux: I perfectly understand this sensitivity, but for me, the problem would be to hide this photograph because of it. Or to hide the fact that Evans was collecting these photographs, or to hide the fact that he was photographing Confederate monuments. Throughout my career, I’ve been dealing with these questions. I’ve published a book on the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. I curated an exhibition and published a book on photography and the Holocaust. I’ve always chosen to show the photograph with, of course, an explanation or with some attention to the way it was displayed in a museum.

In this case it’s a bit different, because that’s not really the subject: this room is not about lynching, it’s about Evans’s own collection. I always take the position that the image is a good way to talk about these questions, and that we should use the image to debate these subjects. The worst thing for me is to hide the images, and the questions that the images raise.

Walker Evans is on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art through February 4, 2018.